Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Can medical tests reliably determine whether my child has ADHD?

No, ADHD is determined by a clinical diagnosis based on interviews and a child’s personal history from teachers, parents, and others who are involved with the child on a day-to-day basis. Research studies using an electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure brain electrical activity, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess brain structure, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure where things happen in the brain have demonstrated some minor differences between the brains of ADHD children and those without ADHD (Question 9). These differences are found in brain regions we think are important for attention. However, EEG,MRI, and fMRI can not be used to make a diagnosis at this time. The findings are not consistent enough to be useful. Perhaps in the future this will change. In addition, even though research studies suggest neurotransmitter and neuroreceptor differences between children with and without ADHD, no blood tests are available to use to make the diagnosis. Although it is possible that researchers will develop some diagnostic laboratory test that can simplify diagnosis, it is unlikely to happen in the near future. Furthermore, even when we document the gene(s) causing ADHD, having the gene will not necessarily mean having ADHD. The human nervous system is just too complex for a simple onetoone effect. Ultimately, a diagnosis of ADHD relies on the experience and judgment of the physician who examines the child, not medical tests or scans.

Monday, May 16, 2011

I took my child to a doctor who made the diagnosis in 30 minutes. Can doctors really make a diagnosis of ADHD that quickly?

Yes. Although parents may have difficulty understanding this, professionals may be able to make the diagnosis of ADHD quite quickly. First, as qualified professionals, they see many children with the same set of critical characteristics. Similar to diagnosing a medical condition, such as diabetes, a personal history in combination with symptoms may quickly point to the right diagnosis. In fact, a child’s personal history alone is often the most important part of the diagnosis. In addition, if you and your child have provided the doctor with completed questionnaires that point out problems with inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity, the diagnosis is often immediately apparent. Very often the history is confirmed by a child’s unruly behavior in the office: however, the key element of the diagnosis is the history, not the inappropriate office behavior.

Sunday, May 15, 2011

Whom do I consult to get a proper diagnosis of ADHD?

A number of different kinds of doctors can diagnose ADHD.Which type you choose to examine your child depends in part on your access to subspecialists and in part on the degree of ADHD and the presence of accompanying disorders. A regular pediatrician or a developmental pediatrician (a pediatrician who specializes in learning issues) can generally manage a child with relatively mild ADHD. Both neurologists and psychiatrists diagnose and treat children with ADHD. Often, they see children whose ADHD is complicated by other medical or psychiatric problems. Pediatricians may refer a patient to either a neurologist or a psychiatrist when the diagnosis is unclear or when they feel that adequately managing an affected child is becoming difficult. A psychiatrist might be a particularly good option for a child with comorbid problems involving oppositional behavior, anxiety, or mood. Conversely, a neurologist might be the right choice for a child with comorbid tics, Tourette’s syndrome, or a specific neurological problem (e.g., seizures).

Although psychologists can not prescribe medication, they can diagnose and treat problems associated with ADHD. However, several types of psychologists are available, and their methods of assessment will differ. Clinical psychologists may use techniques similar to those of a psychiatrist. They will interview parents and child, gaining both historical and current information about developmental, academic, social, and emotional issues and other aspects of the child’s behavior. Other psychologists, usually educational psychologists or neuropsychologists, will use more quantitative measurements to make a diagnosis. Besides following the more typical interview procedures, these clinicians will perform several hours of testing to arrive at a diagnosis. Most certainly, significant school difficulties or outstanding social and emotional issues are symptoms that may warrant a more complete assessment by a psychologist, either through the board of education or on a private basis. In this way, a fuller picture of a child’s particular strengths and weaknesses can be obtained.

Although psychologists can not prescribe medication, they can diagnose and treat problems associated with ADHD. However, several types of psychologists are available, and their methods of assessment will differ. Clinical psychologists may use techniques similar to those of a psychiatrist. They will interview parents and child, gaining both historical and current information about developmental, academic, social, and emotional issues and other aspects of the child’s behavior. Other psychologists, usually educational psychologists or neuropsychologists, will use more quantitative measurements to make a diagnosis. Besides following the more typical interview procedures, these clinicians will perform several hours of testing to arrive at a diagnosis. Most certainly, significant school difficulties or outstanding social and emotional issues are symptoms that may warrant a more complete assessment by a psychologist, either through the board of education or on a private basis. In this way, a fuller picture of a child’s particular strengths and weaknesses can be obtained.

Saturday, May 14, 2011

What are the essential elements of a thorough evaluation to diagnose ADHD?

A thorough evaluation of ADHD requires the recording of a detailed history from parents, a discussion with or observation of the affected child, and some backup evidence from someone outside the home. A qualified doctor can accomplish this at an appointment with you and your child. Although the diagnosis will generally be apparent from a child’s history, an interviewer most likely will ask you, your child, and your child’s teachers to complete appropriate questionnaires.

A detailed history is essential to diagnosing ADHD. It should include information about your child’s birth; illnesses; early language and motor milestones; infant, toddler, and preschool years; educational progress and motivation; homework habits; social interactions and interests; and hobbies and extracurricular activities. A family medical and social history is also important. A detailed history will often include anecdotes that give the doctor a more complete picture of your child’s past and present.

The diagnosis of ADHD requires that the child have symptoms that interfere in at least two settings. By definition, outside sources are required. Although getting a description directly from a teacher—by questionnaire or in person—is useful, parents’ description of what they have been told about classroom behavior often suffices. Sometimes, teacher questionnaires are useful not only for diagnosis, but to show parents how a teacher rates their child’s attention and behavior in a quantitative, rather than a qualitative or descriptive way (such as they would hear at a parent–teacher conference).

A doctor will also try to obtain a complete “picture” of your child. This may involve performing a physical examination, asking questions about school and outside interests, or asking your child to do some simple tasks (e.g., walking on toes and heels or drawing a picture). The objective is to develop an accurate sense of your child for diagnostic purposes.

A detailed history is essential to diagnosing ADHD. It should include information about your child’s birth; illnesses; early language and motor milestones; infant, toddler, and preschool years; educational progress and motivation; homework habits; social interactions and interests; and hobbies and extracurricular activities. A family medical and social history is also important. A detailed history will often include anecdotes that give the doctor a more complete picture of your child’s past and present.

The diagnosis of ADHD requires that the child have symptoms that interfere in at least two settings. By definition, outside sources are required. Although getting a description directly from a teacher—by questionnaire or in person—is useful, parents’ description of what they have been told about classroom behavior often suffices. Sometimes, teacher questionnaires are useful not only for diagnosis, but to show parents how a teacher rates their child’s attention and behavior in a quantitative, rather than a qualitative or descriptive way (such as they would hear at a parent–teacher conference).

A doctor will also try to obtain a complete “picture” of your child. This may involve performing a physical examination, asking questions about school and outside interests, or asking your child to do some simple tasks (e.g., walking on toes and heels or drawing a picture). The objective is to develop an accurate sense of your child for diagnostic purposes.

Friday, May 13, 2011

Often, when I say no, my child overreacts and is defiant or hostile. Is that common for a child with ADHD?

Not every ADHD child is defiant, hostile, or oppositional. However, some are. A certain amount of defiant and oppositional behavior is normal in children of all ages. Yet, it may be a more common or more prominent issue with ADHD children. These children may interrupt and intrude as well as avoid tasks or directions. They may also deliberately annoy other people and blame others for something they themselves do. In fact, accepting responsibility for their behavior may be quite hard for them. However, you must distinguish their inattention and impulsivity from the disruptive behaviors in truly hostile children. Specific characteristics seen in a child with an oppositional defiant disorder include poor temper control, argumentativeness, spitefulness and vindictiveness (“getting even”), resentfulness and anger, and the tendency to rebel against or refuse adult requests. ADHD children can sometimes be defiant and hostile. But, when your ADHD child routinely becomes disruptive and argumentative, it’s time for a professional consultation to determine whether your child has a comorbid disorder. In other words, such children can have two separate problems that occur at the same time.

Thursday, May 12, 2011

Does everyone with attention problems or hyperactivity have ADHD?

No. There are many potential causes for behaviors similar to that seen in ADHD. Children with language disorders who have difficulty understanding and/or expressing themselves can appear inattentive. Their experience may be similar to listening to a foreign language in which words are picked up only here and there. Because they do not always understand what a teacher is saying, such children lose their focus. Consequently, deciding whether a child with language problems also has ADHD can sometimes be difficult. Some children with specific medical problems may also appear to be inattentive. For example, thyroid problems can cause attention difficulties. On the one hand, too little thyroid hormone may cause a child to become inattentive; on the other, too much thyroid hormone may cause hyperactivity. Children with seizures may appear inattentive, but this usually occurs irregularly and only when the seizures are occurring. Children with sleep problems may also appear inattentive because they are so tired during the day. A child with any one of a variety of emotional difficulties may also appear unable to concentrate or may become hyperactive. Children with anxiety or depression sometimes appear preoccupied or distracted. In addition, unlike adults, depressed children may become quite agitated or restless, which can be mistaken for hyperactivity.

As a rule, children with ADHD tend to be distracted by outside stimuli. In contrast, a child with obsessive compulsive disorder or a psychotic illness, for example, may be distracted by internal events, recurring thoughts, and excessive worry. However, a casual observer cannot always tell the difference by the child’s behavior, so it is difficult to correctly identify the source of the problem without careful assessment.

Inattentiveness and hyperactivity also can be side effects of medications. This is particularly common with some of the medications used for treating asthma, particularly theophylline and steroids. Antiseizure medicines can also interfere with attention.

In short, attention problems and hyperactivity are not automatically signs of ADHD, so you should not assume your child has ADHD because you see these behaviors. The child should be assessed by a professional trained to recognize the origins of behavioral problems so that the real cause or causes can be determined.

As a rule, children with ADHD tend to be distracted by outside stimuli. In contrast, a child with obsessive compulsive disorder or a psychotic illness, for example, may be distracted by internal events, recurring thoughts, and excessive worry. However, a casual observer cannot always tell the difference by the child’s behavior, so it is difficult to correctly identify the source of the problem without careful assessment.

Inattentiveness and hyperactivity also can be side effects of medications. This is particularly common with some of the medications used for treating asthma, particularly theophylline and steroids. Antiseizure medicines can also interfere with attention.

In short, attention problems and hyperactivity are not automatically signs of ADHD, so you should not assume your child has ADHD because you see these behaviors. The child should be assessed by a professional trained to recognize the origins of behavioral problems so that the real cause or causes can be determined.

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Do ADHD symptoms in late adolescence put my child at risk for other kinds of problems?

The persistence of ADHD symptoms into adolescence is associated with more academic, behavioral, and social problems. Research indicates that adults with continuing symptoms complete less formal schooling, are employed at the usual rates but have lower-status jobs, and have higher rates of personality disorders. The frequency of substance abuse is higher among adolescents and young adults with continuing ADHD. Coexisting conduct and antisocial personality disorders further increase the risk of substance abuse.

Recent research comparing children who outgrow ADHD to those who remain symptomatic suggests that those with persisting ADHD are more likely to develop other associated illnesses (e.g., conduct and oppositional disorders), which can become increasingly prominent and problematic for these adolescents and young adults. The risk-taking and rule-breaking behavior can also significantly worsen parent–child conflicts.

Among children whose symptoms decrease during adolescence, the outcome is similar to that of non-ADHD individuals regarding occupational achievement, social functioning, and drug and alcohol use, although not academic achievement. Academic issues may remain an affected area even if ADHD disappears.

Recent research comparing children who outgrow ADHD to those who remain symptomatic suggests that those with persisting ADHD are more likely to develop other associated illnesses (e.g., conduct and oppositional disorders), which can become increasingly prominent and problematic for these adolescents and young adults. The risk-taking and rule-breaking behavior can also significantly worsen parent–child conflicts.

Among children whose symptoms decrease during adolescence, the outcome is similar to that of non-ADHD individuals regarding occupational achievement, social functioning, and drug and alcohol use, although not academic achievement. Academic issues may remain an affected area even if ADHD disappears.

Tuesday, May 10, 2011

Are there other signs of ADHD besides the ones traditionally used to establish the diagnosis?

ADHD can show up in children in many ways besides those defined by established criteria in DSM-IV-TR. Social-skill issues may be the presenting symptoms at home and at school. Children may display isolated aggressive behavior in preschool and early elementary school, because of their impulsivity and poor attention to verbal and visual cues. Because their disruptive behavior often results in conflicts with peers, siblings, and authority figures, such children stand out from their classmates. Consequently, they tend to be rejected by their peers. Children with ADHD may also be quite messy and disorganized. Parents frequently describe bedrooms in complete disarray, backpacks with papers falling out, and poor eating habits. General academic difficulties are also common. Children forget their assignments, do not appear to be listening in class, and get poor grades. In addition, they may have what are usually called executive functioning problems: difficulties with planning, starting tasks, shifting from one activity to another, controlling responses, and staying interested and motivated.

Monday, May 9, 2011

Do the symptoms of ADHD change as children mature?

Yes. Although some symptoms persist, many symptoms of ADHD change with development. For example, hyperactivity diminishes in some children after elementary school. Many people think that the hormonal changes of puberty are responsible for this, although we do not understand the mechanism. Older children may have either outgrown their hyperactivity or found ways in which to channel it. A sense of inner restlessness may replace the hyperactivity. In the preteen and adolescent years, poor grades, inability to sustain attention, difficulties in maintaining social relationships, disorganization, and risk-taking behavior may surface as primary symptoms. At school, ADHD may show up more as written work becomes increasingly complex and a teenager is required to plan ahead for long-term assignments. Socially, the range of accepted behavior in many ways is narrowed by the unwritten rules of a teenager’s peer group. The difficulties with emotional self-control and interpersonal communication common in ADHD makes these teenagers appear more immature and clumsy among their peers. Their impulsivity may cause them to blurt out answers inappropriately or to interrupt conversations. They can become disruptive in the classroom or even be perceived as the “class clown.” This can result in peer rejection and subsequent distress in ADHD children.

Sunday, May 8, 2011

At what age might I begin to worry about whether my child has ADHD? Can ADHD be diagnosed in a preschooler?

ADHD can be diagnosed in a child as young as 3 years of age. Signs of ADHD in preschoolers may include a noticeably high activity level, inability to persist with tasks, problems in following group instructions, poor behavior modulation, difficulties with social interactions, unending curiosity, excessive aggression or destructive play, silliness, bossiness, and impulsivity. Preschoolers with ADHD may have sleep problems, such as restless or decreased sleep. In addition, argumentative behavior and temper tantrums may be more common in preschoolers with ADHD. These children may also be quite immature, frequently demonstrating off-task or inappropriate behaviors. All of this can contribute to conflicts within the family, ranging from battles with siblings and parents to difficulties in keeping baby-sitters.

Saturday, May 7, 2011

Could the many ear infections my child had as a toddler be the cause of his ADHD?

Some studies, although not all, have found that children with a history of frequent bilateral ear infections had lower language and speech scores, lower reading scores, and more behavior and attention problems during elementary school. Investigators have suggested that children who suffer from intermittent hearing impairments from ear infections do not get enough “practice” in paying attention. This does not mean that your child will have problems in these areas if he has frequent ear infections, but parents and teachers do need to be vigilant about this problem. It is very unlikely that ADHD is caused by ear infections.

Friday, May 6, 2011

My child with iron-deficiency anemia is hyperactive rather than tired. Is that common?

Anemia, although commonly thought to decrease energy, can be a cause of inattention and hyperactivity during early childhood. Pediatricians routinely monitor for anemia, which is most often caused by iron deficiency. Iron replacement corrects both the anemia and the inattention and hyperactivity fairly quickly.

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Are children born prematurely at increased risk for ADHD?

The frequency of ADHD in children born prematurely is fairly high. One study compared children who had been born prematurely with children who were from the same social class but had been born at full-term. When the children were evaluated at age 7 years, approximately 20% of those in the premature group had ADHD as compared to about 10% of the other group.Many of the premature children who had ADHD also had additional cognitive, neurological, or academic disabilities (e.g., dyslexia and developmental language disorders).

The rapid advances in medical technology have greatly increased the number of children who survive premature birth. However, as more premature babies survive, there is growing evidence that suggests that there are long term repercussions: many of these children—especially the very small ones—develop major neurological problems. These children appear to be at special risk for ADHD because their frontostriatal circuitry is particularly vulnerable to injury owing to its immaturity at the time of birth. It is wise to carefully monitor children who are born premature.

The rapid advances in medical technology have greatly increased the number of children who survive premature birth. However, as more premature babies survive, there is growing evidence that suggests that there are long term repercussions: many of these children—especially the very small ones—develop major neurological problems. These children appear to be at special risk for ADHD because their frontostriatal circuitry is particularly vulnerable to injury owing to its immaturity at the time of birth. It is wise to carefully monitor children who are born premature.

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Can a significant head injury or a minor concussion cause ADHD?

Behavior problems from significant traumatic brain injury include irritability, fatigue, impulsiveness, decreased anger control, disinhibition, decreased motivation, decreased frustration tolerance, decreased initiative, aggressiveness, decreased attention, and hypo- or hyperactivity. This is due at least in part to the fact that a closed-head injury is likely to damage the frontal lobes of the brain. A physician must carefully and indefinitely monitor the classroom attention of a child who has sustained a significant head injury. In contrast, concussions, which are associated with only a brief loss of consciousness, are considered very minor head injuries. Nonetheless, children may have trouble concentrating and focusing for several weeks after a concussion. The effects are transient, but can temporarily affect school performance. Paying attention to the problem will minimize it.

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

What other environmental factors may cause ADHD?

Although environmental factors are most certainly not the main elements leading to ADHD, evidence suggests that exposures to various agents, such as drugs, chemicals, or illnesses, may increase the risk of ADHD. For example, iron-deficiency anemia and thyroid disorders can cause problems with attention span. Exposure to such substances as lead and mercury may also increase the chances of a child having ADHD.

Monday, May 2, 2011

My child with ADHD can sit and watch TV for hours, but I have heard that watching television can cause ADHD. Is this true?

Researchers have recently reported that for every hour a day preschoolers watch television, their risk of developing ADHD increases by about 10%. These new findings are consistent with previous research showing that television can shorten attention spans. Researchers have speculated that TV might actually overstimulate and permanently “rewire” the developing brain.

The newest study on TV watching assessed more than 1000 children. Parents were questioned about the children’s TV watching habits at 1 and 3 years of age. They rated their children’s behavior at age 7 years on a scale commonly used to diagnose ADHD. About 10% met criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD, about the same frequency as is usually found in 7-year-olds. But the 37% of 1-year-olds who watched 1 to 2 hours daily had a 10% to 20% increased risk of attention problems; the 14% who watched 3 to 4 hours daily had a 30% to 40% increased risk compared with children who watched no TV. Among 3-year-olds, only 7% watched no TV, 44% watched 1 to 2 hours daily, 27% watched 3 to 4 hours daily, almost 11% watched 5 to 6 hours daily, and about 10% watched 7 or more hours daily. These children too were at increased risk for ADHD, and the risk was proportionate to how much TV they watched. Although the research has been done on TV watching, the effects of any repetitive non-educational activity or electronic device, such as playing video games, may be the same.

The TV research is compelling enough that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that parents do not permit children under 2 years of age to watch television because of concerns that it affects early brain growth and the development of social, emotional, and cognitive skills. And there are many other reasons that children should not watch television. For example, TV watching has been associated with obesity and aggressiveness. So, even if it is one of the places your ADHD child will sit quietly, it is best to limit TV watching. You need to be creative about finding other things your child would like to do. Reading to your child or encouraging your child to read alone, even if he is reading sports magazines or comic books, is a better alternative.

The newest study on TV watching assessed more than 1000 children. Parents were questioned about the children’s TV watching habits at 1 and 3 years of age. They rated their children’s behavior at age 7 years on a scale commonly used to diagnose ADHD. About 10% met criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD, about the same frequency as is usually found in 7-year-olds. But the 37% of 1-year-olds who watched 1 to 2 hours daily had a 10% to 20% increased risk of attention problems; the 14% who watched 3 to 4 hours daily had a 30% to 40% increased risk compared with children who watched no TV. Among 3-year-olds, only 7% watched no TV, 44% watched 1 to 2 hours daily, 27% watched 3 to 4 hours daily, almost 11% watched 5 to 6 hours daily, and about 10% watched 7 or more hours daily. These children too were at increased risk for ADHD, and the risk was proportionate to how much TV they watched. Although the research has been done on TV watching, the effects of any repetitive non-educational activity or electronic device, such as playing video games, may be the same.

The TV research is compelling enough that the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that parents do not permit children under 2 years of age to watch television because of concerns that it affects early brain growth and the development of social, emotional, and cognitive skills. And there are many other reasons that children should not watch television. For example, TV watching has been associated with obesity and aggressiveness. So, even if it is one of the places your ADHD child will sit quietly, it is best to limit TV watching. You need to be creative about finding other things your child would like to do. Reading to your child or encouraging your child to read alone, even if he is reading sports magazines or comic books, is a better alternative.

Sunday, May 1, 2011

Was my child born with ADHD, or did it “develop?”

In most cases, to the extent that ADHD is a genetic disorder, your child was born with ADHD. In other words, the genes that contribute to the disorder were present at birth. Some children born with the genes for the disorder do not develop ADHD symptoms at all; some have such slight difficulties with attention that it goes undetected throughout their lives. Nevertheless, the signs can appear and change over time, depending on a variety of circumstances. Environmental factors play a role even when the main cause is genetic. A child with a mild disorder can subsequently manifest extreme inattention or hyperactive behavior in the presence of certain environmental factors, such as parental abuse or neglect, poor living conditions, or other circumstances that stress children emotionally. If ADHD symptoms develop “suddenly,” it is likely that the disorder was present but hidden, only appearing when an environmental factor came into play.

Saturday, April 30, 2011

Do nongenetic risk factors for ADHD exist?

Results from a large national study performed in the 1960s indicated that a number of nongenetic factors can affect the risk of ADHD. The children evaluated in that study were followed from conception until 7 years of age. Risk factors for ADHD included a history of smoking, alcohol use, drug use or anemia during pregnancy, breech birth, chorioamnionitis (infection of the placenta) during labor, premature birth, and small head size at birth. A family history of mental retardation and low socioeconomic status also appeared to be risk factors. Neurological problems in the first month of life increase the risk of ADHD at age 7 years from 2% to 50%. In infancy, delayed development and increased activity predict ADHD at age 7 years.When a 4-yearold child has a small head size, astigmatism, or visual motor, fine motor, or gross motor deficits, the risk of ADHD is increased.

Psychosocial problems at home are also risk factors for ADHD. A Hawaiian study revealed a 200% to 400% increased risk of ADHD in children from families where there was a lot of conflict in the home. In a Swedish study, unsatisfactory family life was the largest risk factor for ADHD, overriding any other medical problems.

Having a risk factor or even several risk factors does not mean that ADHD is going to occur, but it makes ADHD more likely than in someone who has no risk factors. The various risk factors predispose a child to ADHD to different degrees.

Psychosocial problems at home are also risk factors for ADHD. A Hawaiian study revealed a 200% to 400% increased risk of ADHD in children from families where there was a lot of conflict in the home. In a Swedish study, unsatisfactory family life was the largest risk factor for ADHD, overriding any other medical problems.

Having a risk factor or even several risk factors does not mean that ADHD is going to occur, but it makes ADHD more likely than in someone who has no risk factors. The various risk factors predispose a child to ADHD to different degrees.

Friday, April 29, 2011

If I have ADHD, will my child also have it?

No, not necessarily, but the chance is definitely greater than if you did not have ADHD. For example, onethird of fathers with a history of ADHD in childhood have a child with ADHD. For mothers, the percentage is somewhat lower. Sometimes, it is a male relative in the mother’s family who has ADHD. Mothers presumably have the ADHD gene, but they may exhibit few or no symptoms. Nonetheless, these mothers can pass the ADHD gene on to their children.We are still not sure why females are less likely to have ADHD symptoms, even when it is almost certain they have one of the ADHD genes. In one study of ADHD adults and controls, 43% of children with ADHD parents met criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD, compared to 2% of children in the control group of children who had parents without ADHD. If your first child has ADHD, the risk of your second child having ADHD is probably higher than in the general population. However, predicting the severity of ADHD or the type of ADHD that might run in a family is not possible.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

What causes ADHD?

By far, the most common cause of ADHD is a genetic proclivity (i.e., ADHD is often inherited). Studies suggest that the heritability rate of ADHD ranges from 0.75 to 0.91. The heritability rate indicates the percentage of ADHD in an individual resulting from genetic rather than environmental factors. Thus, a heritability rate of 0.75 means that 75% of the cause of ADHD is genetic.However, ADHD can also be caused or exacerbated by other factors, such as preterm birth, anemia, medications for asthma, and other environmental factors.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Would I know any famous people who have or have had ADHD?

Most certainly ADHD has affected the lives of all kinds of people including authors, inventors, military leaders, statesmen, composers, athletes, and actors and actresses. The following list includes individuals who may or may not have had diagnosed ADHD but who most certainly exhibited behavior that indicates the possible presence of ADHD or other learning disabilities. For example, Danny Glover, Bill Cosby,Tom Cruise, Jim Carrey, Robin Williams, Nolan Ryan, Jason Kidd, and Magic Johnson are all individuals who have been described as having ADHD symptoms. Many very successful entrepreneurs, such as Walt Disney and Malcolm Forbes, have also proved that their ability to “think outside the box” was perhaps a more positive consequence of ADHD. In fact, many individuals who have excelled at multitasking may have been using features of their ADHD in a positive way; their difficulties in focusing on a single task improved their ability to handle many tasks at once.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Does having ADHD mean that something is fundamentally wrong with my child’s brain?

ADHD is a biological, brain-based problem, but that’s not the same as saying that something is wrong with your child’s brain. There’s a big difference between damage and dysfunction. Damage causes problems with the “hardware” or the basic brain structures. That’s not what happens in ADHD. Although research data show that some brain structures, particularly the caudate, the corpus callosum (which allows the two hemispheres to “talk” to each other), and the cerebellum may be smaller in children with ADHD, but there is no indication that damage per se is present. In ADHD, the primary problem is with the “software”: the wiring or the connections in the brain. The problem with the connections most likely can be traced to atypical amounts of specific neurotransmitters, either individually or in relation to one another.

One recent imaging study showed that children with ADHD have relative cortical thinning in regions important for attention. Children with persistent ADHD had “fixed” thinning of areas of the frontal cortex, which may compromise the maturation of attentional systems. On the other hand, cortical thickness normalized in children who “outgrow” their ADHD.

One recent imaging study showed that children with ADHD have relative cortical thinning in regions important for attention. Children with persistent ADHD had “fixed” thinning of areas of the frontal cortex, which may compromise the maturation of attentional systems. On the other hand, cortical thickness normalized in children who “outgrow” their ADHD.

Monday, April 25, 2011

What genes are involved in ADHD?

You may be aware that many functions in our body, including production of hormones and other body and brain chemicals, are controlled by specific genes—the molecules of DNA that tell our cells how to develop and behave. You may not, however, have a clear idea of how this really works, and the fact is that scientists did not either until fairly recently. Mapping the human genome has helped determine some of the genes controlling specific functions, but many genes affect body systems in ways that scientists have yet to figure out. In some cases, multiple genes may be involved in complex interactions to cause an organ or a system to function properly (or improperly, as in the case of ADHD and many other disorders).

Genetic studies of ADHD have focused largely on genes involved in controlling the neurotransmitter dopamine. This is logical because medications that increase dopamine are effective treatments for ADHD. Furthermore, brain-imaging studies have identified abnormalities in the dopamine-rich frontal and striatal regions in individuals with ADHD. In animal models used to investigate ADHD, “knock-out” mice—mice missing a gene important for increasing dopamine—are hyperactive and do not respond to stimulant treatment. Their dopamine can not be increased, and they remain hyperactive.

Currently the genes most likely to cause ADHD are thought to involve dopamine regulation. The dopamine transporter (DAT) gene is the prime candidate. This gene regulates the amount of dopamine in the synapse by determining how much dopamine is reabsorbed into the presynaptic neurons. In controls, the dopamine transporter keeps the level of dopamine in the synapse relatively high. In ADHD, the DAT “overfunctions” and lowers the level of synaptic dopamine. Stimulants inhibit DAT. As a result, more dopamine remains in the synapse. Other possible causal genes control postsynaptic dopamine receptors. They affect the sensitivity of the receptors to dopamine. It may take more dopamine to activate the postsynaptic receptors in children with ADHD.

So what does this knowledge mean for treating children with ADHD? First, it may help scientists design better medications for treating ADHD. They can target the cause of the neurotransmitter problem. Second, scientists can work toward treatments, called gene therapy, that correct the genetic abnormalities by replacing the abnormal gene. Gene treatment is currently being tried for a number of serious progressive neurological disorders.

Genetic studies of ADHD have focused largely on genes involved in controlling the neurotransmitter dopamine. This is logical because medications that increase dopamine are effective treatments for ADHD. Furthermore, brain-imaging studies have identified abnormalities in the dopamine-rich frontal and striatal regions in individuals with ADHD. In animal models used to investigate ADHD, “knock-out” mice—mice missing a gene important for increasing dopamine—are hyperactive and do not respond to stimulant treatment. Their dopamine can not be increased, and they remain hyperactive.

Currently the genes most likely to cause ADHD are thought to involve dopamine regulation. The dopamine transporter (DAT) gene is the prime candidate. This gene regulates the amount of dopamine in the synapse by determining how much dopamine is reabsorbed into the presynaptic neurons. In controls, the dopamine transporter keeps the level of dopamine in the synapse relatively high. In ADHD, the DAT “overfunctions” and lowers the level of synaptic dopamine. Stimulants inhibit DAT. As a result, more dopamine remains in the synapse. Other possible causal genes control postsynaptic dopamine receptors. They affect the sensitivity of the receptors to dopamine. It may take more dopamine to activate the postsynaptic receptors in children with ADHD.

So what does this knowledge mean for treating children with ADHD? First, it may help scientists design better medications for treating ADHD. They can target the cause of the neurotransmitter problem. Second, scientists can work toward treatments, called gene therapy, that correct the genetic abnormalities by replacing the abnormal gene. Gene treatment is currently being tried for a number of serious progressive neurological disorders.

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Where in the brain do neurotransmitters have their effects?

Neurotransmitters are chemicals in your brain that pass along information from one cell to another. Neurotransmitters act in the synapse, the space between two brain cells (neurons). Neurotransmitters released by presynaptic neurons act on receptors on postsynaptic neurons (Figure 3). The amount of neurotransmitter in the synaptic space and the sensitivity of the postsynaptic cell receptors determine the neurotransmitter’s effect on the postsynaptic brain cell.

There are many different neurotransmitters. Although dopamine is probably the neurotransmitter that is maximally involved in ADHD, norepinephrine and serotonin probably play lesser roles. The relative balance among these neurotransmitters may be as important as their absolute amounts. Dopamine is the main neurotransmitter in the striatum, while norepinephrine is the main neurotransmitter in the frontal lobe.

There are many different neurotransmitters. Although dopamine is probably the neurotransmitter that is maximally involved in ADHD, norepinephrine and serotonin probably play lesser roles. The relative balance among these neurotransmitters may be as important as their absolute amounts. Dopamine is the main neurotransmitter in the striatum, while norepinephrine is the main neurotransmitter in the frontal lobe.

Saturday, April 23, 2011

What parts of the brain are affected in ADHD?

In studies of ADHD children, the structures that most often have been found to play a role are the frontal lobes, the striatum (particularly the caudate), and the connection between these structures, which is called the frontostriatal circuitry. More recently, the cerebellum has also been found to play a role in ADHD (Figure 1).

If you are not a neurologist, that explanation probably does not mean much, so here is a quick lesson in brain anatomy and function. Your brain is made up of four lobes: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital. By and large, the frontal lobes control executive functioning (e.g., planning, organizing, starting, persisting, shifting, and inhibiting impulsive behaviors). The parietal lobes control sensory functions and spatial skills (especially the right parietal lobe). The temporal lobes control language comprehension and memory, and the occipital lobes control vision. The left frontal lobe has the bigger effect on language-related executive functions, and the right frontal lobe has more of an influence on spatial executive function (Figure 2).

The striatum is made up of a number of structures deep within the brain, the caudate being the most active in ADHD. In healthy individuals, the striatum is rich in dopamine. Some structures in the striatum play a significant role in motor function. Parts of the striatum are low in dopamine in such movement disorders as Parkinson’s disease, leading to tremors and very slow movements. Parts of the striatum have also been found to be involved in tic disorders.

The frontostriatal circuitry forms the connection between the frontal lobes and parts of the striatum. Brain cells connect these structures, and the connection is maintained by information passed between the cells via neurotransmitters.

Finally, the cerebellum is part of the hindbrain and has been thought to primarily handle coordination. However, recent studies suggest it plays an important role in cognitive functions, such as language and attention, as well as motor planning. Cerebellar striatal frontal circuitry may also play a role in ADHD.

If you are not a neurologist, that explanation probably does not mean much, so here is a quick lesson in brain anatomy and function. Your brain is made up of four lobes: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital. By and large, the frontal lobes control executive functioning (e.g., planning, organizing, starting, persisting, shifting, and inhibiting impulsive behaviors). The parietal lobes control sensory functions and spatial skills (especially the right parietal lobe). The temporal lobes control language comprehension and memory, and the occipital lobes control vision. The left frontal lobe has the bigger effect on language-related executive functions, and the right frontal lobe has more of an influence on spatial executive function (Figure 2).

The striatum is made up of a number of structures deep within the brain, the caudate being the most active in ADHD. In healthy individuals, the striatum is rich in dopamine. Some structures in the striatum play a significant role in motor function. Parts of the striatum are low in dopamine in such movement disorders as Parkinson’s disease, leading to tremors and very slow movements. Parts of the striatum have also been found to be involved in tic disorders.

The frontostriatal circuitry forms the connection between the frontal lobes and parts of the striatum. Brain cells connect these structures, and the connection is maintained by information passed between the cells via neurotransmitters.

Finally, the cerebellum is part of the hindbrain and has been thought to primarily handle coordination. However, recent studies suggest it plays an important role in cognitive functions, such as language and attention, as well as motor planning. Cerebellar striatal frontal circuitry may also play a role in ADHD.

Friday, April 22, 2011

Do children outgrow ADHD?

Many children do outgrow ADHD. However, the latest data suggest that 50% to 70% of children continue to have some symptoms of ADHD in adolescence, and as many as 50% have persistent ADHD in adulthood. However, even in persistent cases, the number of symptoms decrease during adolescence and usually decrease further in adulthood. The types of symptoms also change. Hyperactivity and impulsivity tend to disappear, although adults with ADHD will often comment on their mental as opposed to physical restlessness. From a biological vantage point, the reduction of symptoms probably reflects brain maturation that continues through adolescence and beyond.

Thursday, April 21, 2011

At what age does ADHD most often surface?

The disorder affects individuals of all ages. Of the millions of visits for ADHD to community physicians, about 5% are preschoolers, approximately 66% were elementary school-age, 20% were teenagers, and 15% were adults. ADHD is, however, most often diagnosed in elementary school-age children. Some children are diagnosed later during their junior high school and high school years. It also is not unusual for individuals to receive their first diagnosis of ADHD as adults. Interestingly, many parents first recognize that they have ADHD when it is diagnosed in their child. As this disorder was not diagnosed very frequently years ago, many individuals went through their school years with undiagnosed ADHD. Subsequently, when parents see their children experiencing similar difficulties, they remember their own history, are able to relate, and confirm their own undiagnosed disorder.

ADHD can be diagnosed in preschoolers. Indeed, the peak age of onset, which is different from the age at diagnosis, may be between ages 3 and 4. Not surprisingly, severity affects the age at which ADHD is first noticed, with those more severely affected presenting at a younger age.

ADHD can be diagnosed in preschoolers. Indeed, the peak age of onset, which is different from the age at diagnosis, may be between ages 3 and 4. Not surprisingly, severity affects the age at which ADHD is first noticed, with those more severely affected presenting at a younger age.

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

Do different types of ADHD exist?

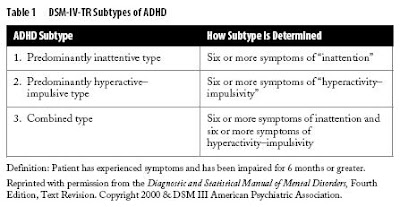

Yes. The DSM-IV-TR identifies three subtypes of ADHD (Table 1). Some children have symptoms that suggest a mainly hyperactive–impulsive type. To meet criteria for this subtype, a child must exhibit six or more symptoms (including restlessness, frequent interrupting, or talking excessively; see Table 2 for the list of core symptoms). The second subtype emphasizes inattention. To have a diagnosis of this subtype of ADHD, a child must have difficulty following directions, fail to pay close attention to details, be forgetful in daily activities, or become easily distracted. In the third subtype, the combined type, a child must display six or more symptoms of both inattention and of hyperactivity–impulsivity.

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

How common is ADHD?

ADHD is quite common; it is conservatively estimated to affect 3% to 5% of school-age children. Some reports suggest that as many as 4% to 8% or even an amazing 10% to 18% of children have ADHD. Thus, somewhere between 2 and 13 million American children have ADHD. Put another way, on the average, at least one child in every classroom has ADHD. ADHD results in millions of physician visits per year.

Approximately 60% of children with ADHD have symptoms that persist into adulthood. This means that close to 8 million adults (about 4% of the U.S. adult population) have ADHD. However, as ADHD is a behavioral disorder still lacking a specific biological marker, estimates of its frequency can be affected by a number of factors.

The method for making the diagnosis most certainly affects the estimated frequency. The current DSM-IV-TR standards, which allow both hyperactive–impulsive and inattentive subtypes, have resulted in higher rates of diagnosis than previous DSM standards, which placed a higher emphasis on hyperactivity as a diagnostic criterion. In other words, the frequency of the diagnosis increases when hyperactivity is not regarded as a necessary characteristic for ADHD diagnosis. The looser the requirements are, the greater the number of individuals included under the diagnostic umbrella.

The estimated frequency of ADHD also depends on who provides the information to make the diagnosis: parent, teacher, child, or physician. All have their own agendas to report. Teachers are seeing children through the lens of the classroom, where there are specific academic and behavioral expectations. In a class full of children, disruption by a single student can have a ripple effect. On the other hand, in a large class full of children, teachers may not notice the quietly inattentive child. Children may be less aware of their own symptoms. Adolescents, in particular, are notorious for underreporting and minimizing their symptoms. Parents view their children’s behavior from the perspective of day-in, day-out living. Their perspective is intensive as well as long-term. On the one hand, they may minimize symptoms that they have been living with for years. On the other hand, the behavior seen under the intensive lens of daily living may make them keenly aware of things that go unnoticed by others. Physicians see children in a rather artificial setting, where the child is the focus of attention and may be on his or her best behavior. Conversely, some children are stressed by a visit to the doctor and will immediately demonstrate ADHD-like signs by wandering around the office, touching and picking up everything in sight.

Approximately 60% of children with ADHD have symptoms that persist into adulthood. This means that close to 8 million adults (about 4% of the U.S. adult population) have ADHD. However, as ADHD is a behavioral disorder still lacking a specific biological marker, estimates of its frequency can be affected by a number of factors.

The method for making the diagnosis most certainly affects the estimated frequency. The current DSM-IV-TR standards, which allow both hyperactive–impulsive and inattentive subtypes, have resulted in higher rates of diagnosis than previous DSM standards, which placed a higher emphasis on hyperactivity as a diagnostic criterion. In other words, the frequency of the diagnosis increases when hyperactivity is not regarded as a necessary characteristic for ADHD diagnosis. The looser the requirements are, the greater the number of individuals included under the diagnostic umbrella.

The estimated frequency of ADHD also depends on who provides the information to make the diagnosis: parent, teacher, child, or physician. All have their own agendas to report. Teachers are seeing children through the lens of the classroom, where there are specific academic and behavioral expectations. In a class full of children, disruption by a single student can have a ripple effect. On the other hand, in a large class full of children, teachers may not notice the quietly inattentive child. Children may be less aware of their own symptoms. Adolescents, in particular, are notorious for underreporting and minimizing their symptoms. Parents view their children’s behavior from the perspective of day-in, day-out living. Their perspective is intensive as well as long-term. On the one hand, they may minimize symptoms that they have been living with for years. On the other hand, the behavior seen under the intensive lens of daily living may make them keenly aware of things that go unnoticed by others. Physicians see children in a rather artificial setting, where the child is the focus of attention and may be on his or her best behavior. Conversely, some children are stressed by a visit to the doctor and will immediately demonstrate ADHD-like signs by wandering around the office, touching and picking up everything in sight.

Monday, April 18, 2011

Does gender have an effect on ADHD in children?

Most studies indicate that more boys than girls have ADHD. The ratio is probably 2–3:1 in school-age children. One study that researched the frequency of ADHD in school-aged children in the United States found the rate in boys was 9% compared to a rate of 3% in girls. Age seems to have an effect on the gender ratio. The male:female ratio drops in adolescence toward 1:1. In fact, some adult studies even suggest that women have ADHD more often than men. As hyperactivity lessens, the inattentive form of ADHD more commonly seen in girls may persist and equalize the ratio.

Bear in mind, however, that these study results are determined by the detection of ADHD. Gender ratios may be affected by referral practices. Among children referred to child psychiatrists or psychologists, the boy–girl ratio varies from 3:1 to 9:1, whereas in community surveys of school-age children, it is closer to 2:1. More severely or obviously affected children are probably referred to a specialist and are usually boys. It is possible, however, that ADHD goes undetected in girls more often than it does in boys. In this regard, it is important to note that boys and girls tend to have different types of ADHD. Boys more often have the hyperactive–impulsive type or the combined type, whereas girls more often have the inattentive type. Some people suggest that this difference affects the frequency with which ADHD is picked up. In other words, boys could receive diagnoses more often because they are more vocal, their problematic behavior is more obvious, and they are more troublesome for their teachers and families. Although girls tend to be affected less often than are their male peers, some studies suggest that those with diagnosed ADHD tend to be less bright and have more academic difficulties than do boys with ADHD. It is possible that very bright girls simply compensate better and their ADHD goes undetected.

Bear in mind, however, that these study results are determined by the detection of ADHD. Gender ratios may be affected by referral practices. Among children referred to child psychiatrists or psychologists, the boy–girl ratio varies from 3:1 to 9:1, whereas in community surveys of school-age children, it is closer to 2:1. More severely or obviously affected children are probably referred to a specialist and are usually boys. It is possible, however, that ADHD goes undetected in girls more often than it does in boys. In this regard, it is important to note that boys and girls tend to have different types of ADHD. Boys more often have the hyperactive–impulsive type or the combined type, whereas girls more often have the inattentive type. Some people suggest that this difference affects the frequency with which ADHD is picked up. In other words, boys could receive diagnoses more often because they are more vocal, their problematic behavior is more obvious, and they are more troublesome for their teachers and families. Although girls tend to be affected less often than are their male peers, some studies suggest that those with diagnosed ADHD tend to be less bright and have more academic difficulties than do boys with ADHD. It is possible that very bright girls simply compensate better and their ADHD goes undetected.

What is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)?

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a disorder in which a child displays hyperactive, impulsive, and/or inattentive behavior that is age-inappropriate. ADHD is a result of an atypical chemical balance in the brain, which means that ADHD is a physical problem, not an emotional problem. Outside factors, such as poor parenting, a chaotic home situation, divorce, or school stresses may affect how the symptoms come to light, but they do not cause ADHD. In order to diagnose ADHD (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision [DSM-IV-TR]), problems of inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity must interfere with a child’s functioning in at least two settings (home, school, or social situations). In addition, the guidelines state that at least some symptoms must have been present before the age of 7 years.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)